Award-Winning Photographer Earl Dotter Shows the Face of Asbestos Workers

Written by Tara Strand on August 10, 2016

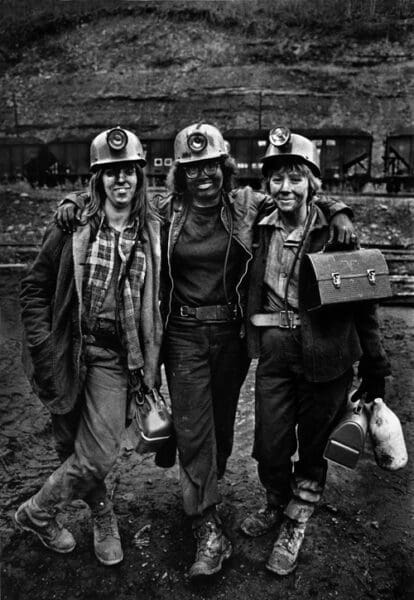

Earl Dotter is an award-winning photojournalist who has spent the last four decades documenting the American laborer. Starting in the coalfields of Appalachia in the late 1960s, Dotter has focused much of his career on not only telling the stories of industrial workers, but also using his photography as a tool to spur change in the conditions in which his subjects toil daily. His efforts have earned him a host of awards and recognitions, up to and including a more than decade-long visiting scholar appointment at The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the entry of his photograph series on coal mining into the Permanent Collection of the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institute.

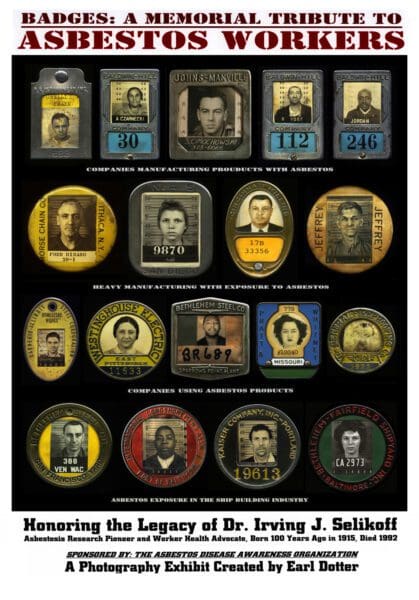

Dotter’s most recent project was inspired by the photo ID badges that asbestos workers used to wear. Titled “Badges: A Memorial Tribute to Asbestos Workers,” Dotter says he got the idea for the exhibit when he realized that a number of badges he had collected from various workers over the years came from places where asbestos had been mined, manufactured, or otherwise used by workers (such as in construction, shipbuilding, etc.).

Mesothelioma.com recently had the opportunity to interview Dotter about the “Badges” exhibit and the work he has done to help American workers.

Mesothelioma.com: Recently, you have been capturing images of patients during their treatment, and their activism efforts to ban asbestos. Why is using photos a good way to tell these stories?

Dotter: My pictures personalize subjects I photograph and stress the common ground between them and the viewers who look upon them. It is easier to care about someone you are acquainted with. I hope my photographs do that and that they also command the attention of those individuals who might ordinarily pass them by.

Mesothelioma.com: As you mentioned in your Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization (ADAO) interview, your college photo instructor required you to take photographs expressing your personal point of view. What is your point of view when it comes to occupational workers and their health concerns/risks?

Dotter: Each of us responds to the world around them in ways that relate to who we are as individuals. The camera literally gives me an excuse to poke my nose into other people’s business. As a kid, I was painfully shy, so the camera helped me connect with people that I was interested in. Before long, I discovered most all my subjects were hard working human beings.

I believe everyone should have a chance to reach their fullest potential. If in my subject’s employment or work experience they have been diminished, I need to show the causes of that diminishment, wherever that takes me. If on the other hand, a subject’s work experience has enhanced them, I need to show that too.

Mesothelioma.com: You’re invited to travel all over the country to present your images to a wide variety of people. What do you hope people take away from these exhibits?

Dotter: I hope my photographs show the enhanced value in lives that have been enriched by their work experience. I also hope to reveal how we as a society lose out when lives are lost or impaired at work. I seek to return to my subjects with the exhibits I have created about them. I hope to show through photos how workers can learn more effective ways to perform their jobs in safer and healthier ways, from one another.

I learned from my early graphic design training that a positive message is almost always more effective than a negative message. As the book title said: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men – and women!

Mesothelioma.com: Are there any particular reactions to your exhibits that have stuck with you?

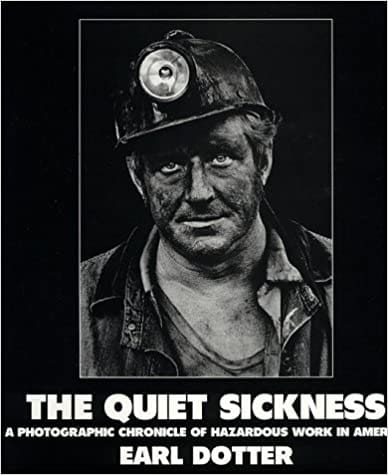

Dotter: I was particularly proud to hear from industrial hygienists when I first showed my QUIET SICKNESS exhibit at their 1997 annual meeting in Washington, D.C., that the exhibit reconnected them with their original motivation for entering the profession. 10,000 IH’s viewed the exhibit and I was awarded a book contract on the spot, as a result, for The Quiet Sickness: A Photographic Chronicle of Hazardous Work in America.

Mesothelioma.com: Do you ever build an exhibit for a specific reaction, or is it made to only tell a story?

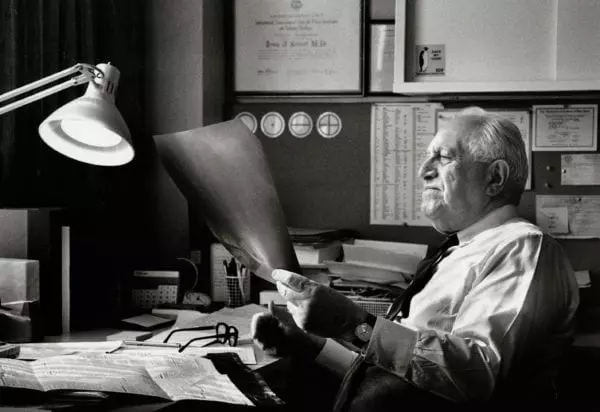

Dotter: Often, I create an exhibit to seize an opportunity to work in a particular subject area where I have not done significant work. The idea for the BADGES: A Memorial Tribute to Asbestos Workers exhibit, came about because I had photographed the good asbestos doctor, Irving Selikoff, back in 1990 and by 2014 had collected many workplace photo ID badges from the legions of workers who had been exposed to asbestos in the job.

These badges personalized this large group of harmed ship builders, construction insulation workers and more recently the 9/11 emergency responders I had photographed on Ground Zero. Also, 2015 was the centennial of Selikoff’s birth. So I proposed to the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization that I create a portable traveling exhibit to continue to raise awareness about the unfortunate history of asbestos and to show the present ongoing travail that 10,000 to 12,000 new asbestos disease victims face here annually in the U.S.

In 1990, you photographed Dr. Irving Selikoff (the medical researcher who discovered a link between mesothelioma and asbestos) at the Mount Sinai Medical Center. What insights did you gain from spending that time with him?

Dotter: I admire Dr. Irving Selikoff because of his through medical research linking asbestos exposure to asbestos disease and thereby proving that it took 20 to 30 years for this lethal disease to manifest itself in in exposed workers. Furthermore, Selikoff stepped way out of his medical research comfort zone to become an asbestos ban advocate testifying before Congress and personally buttonholing politicians.

So, largely because of Selikoff’s work, asbestos victims no longer had their claims against the asbestos industry thrown out of court because the statute of limitations no longer applied with asbestos disease, but also because of Selikoff, asbestos is no longer in brakes, in our home insulation, or on our plumbing or in our workplaces, with just a few remaining exceptions that also require a ban today.

Mesothelioma.com: After going around and immersing yourself in so many people’s life stories, have you ever considered having someone photograph your journeys?

Dotter: Fortunately Deborah Stern, my wife of 31 years, a former assistant general counsel of the United Mine Workers Union, is a fine photographer and has begun to do just that.

Mesothelioma.com: How does the subject of your photographs affect your choice of the technical devices or techniques that you use?(e.g. color vs. monochrome, filters, etc?)

Dotter: I subscribe to the design adage: “Form follows function.” So the equipment that allows me the opportunity to collaborate with my subjects, I will use. I like to first learn from my subjects before developing any picture taking strategy. I have to introduce myself, let them know who I am and why I want to take their picture. It is what I call common courtesy. If I do that first, then maybe the favor will be returned.

So rarely will I use a telephoto lens. My subjects know why I want to photograph them, so if I am onboard with them they have a bit more patience with the process. And I can show, right then, what I am doing on my digital camera to encourage their participation. With digital it is also much easier to give images back to my subjects.

Mesothelioma.com: Which photograph from your current exhibit is your favorite or the most memorable to you?

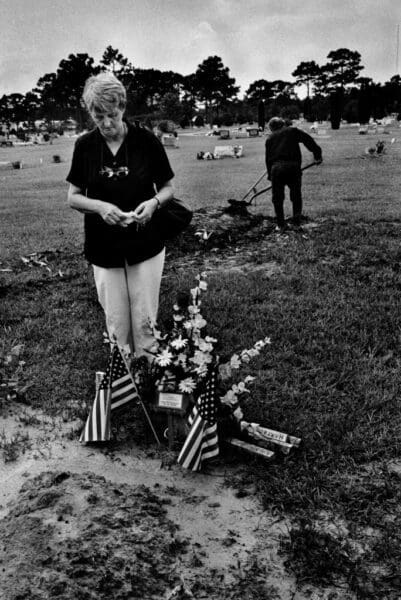

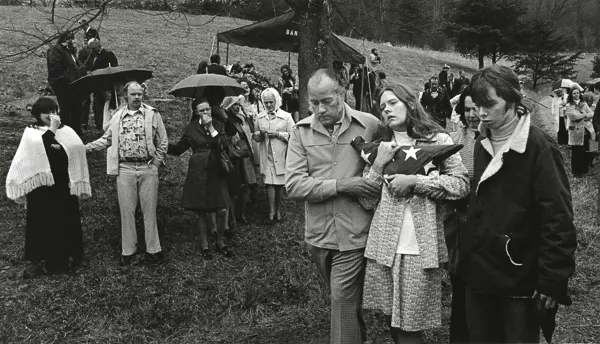

Dotter: It is the picture that got me my wife! Deborah Stern saw the image in the last years of her legal education in an American Photographer magazine feature called: Coal Miner’s Dotter. It is of a pregnant Elizabeth Griffin as she left her husband’s graveside. Her husband Robert, had recently been discharged from Vietnam, and had died in the Scotia Coal Mine Disaster in Oven Fork, KY, which also claimed the lives of 25 other miners in two explosions underground. This photo induced Deborah Stern to seek employment with the UMWA, where she found me. So instead of purchasing this photo from me she married the whole collection.

Mesothelioma.com: Your work has taken you to some very emotional environments. What drives you to continue taking pictures that portray so many feelings that words could never describe?

Dotter: Most of us spend a third of our lives making a living. It is a noble pursuit, supporting yourself and your family. Not too many photographers carve out this subject area as their own today and I still can’t figure out why. Sometimes, when entering a factory, I feel like I am on a movie set with colorful actors of all descriptions populating the moving stage. But what is even better, is it is real and also is a visually engaging opportunity for me to do useful work too.

Mesothelioma.com: What is the most challenging aspect about photographing in such dangerous environments?

Dotter: I never feel as vulnerable as those individuals I photograph on the job. They do it every day, day in, day out. I am just there for the briefest of moments in their working lives, and I usually have very good people watching my back. My working days are always new, different, personal and visually inspiring. I feel I have a privileged and exciting working life.

Free Mesothelioma Treatment Guide

Tara Strand specializes in writing content about mesothelioma and asbestos. She focuses on topics like mesothelioma awareness, research, treatment, asbestos trust funds and other advocacy efforts.